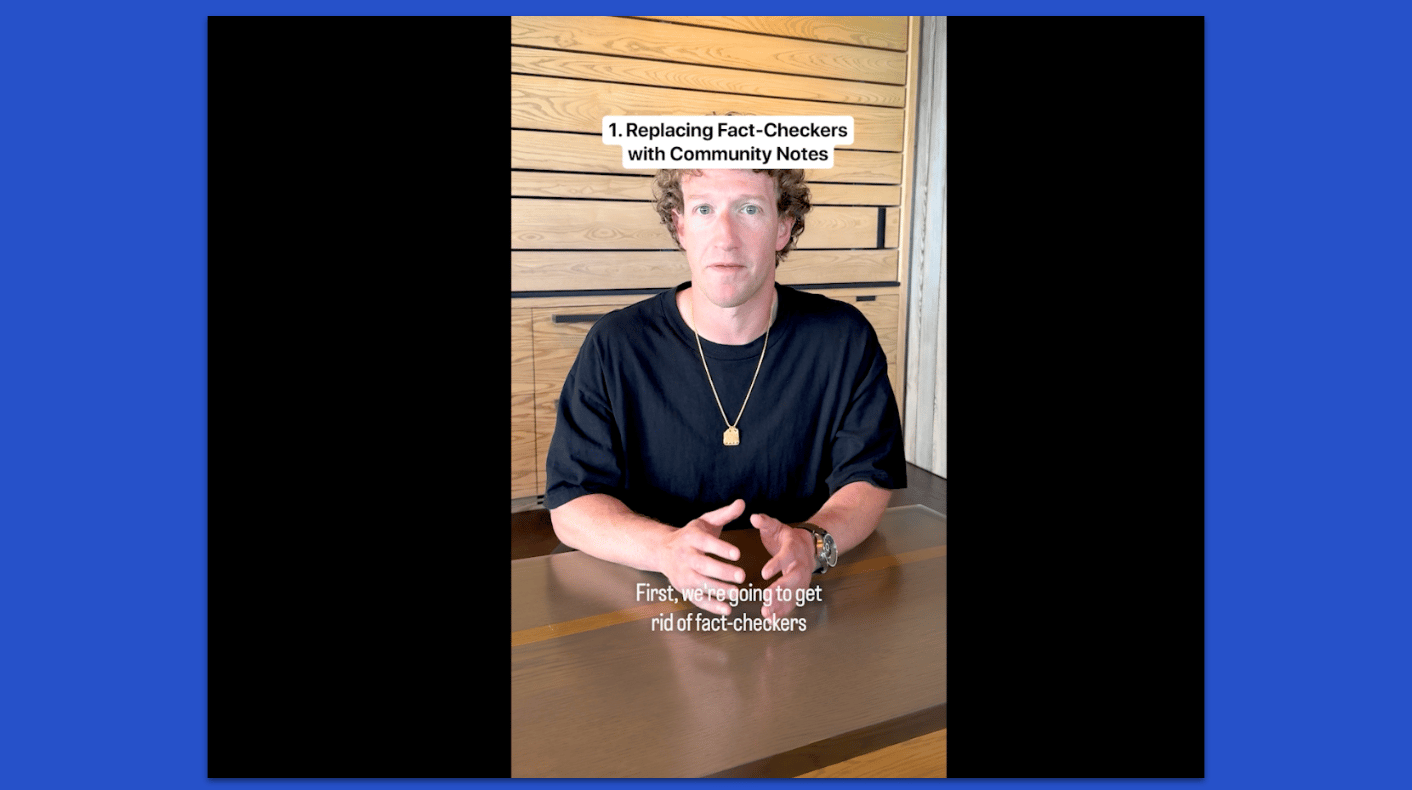

On January 7, Mark Zuckerberg posted a video on Facebook.

“There’s been widespread debate about potential harms from online content,” he said. “Governments and legacy media have pushed to censor more and more. A lot of this is clearly political. But there’s a lot of legitimately bad stuff out there.”

Zuckerberg said that Meta’s moderation systems were making too many mistakes and censoring content. He announced the end of Meta’s third-party fact-checking program in the US and said the company would roll back some moderation systems. Zuckerberg accused fact checkers of being “too politically biased" and said they have “destroyed more trust than they created.”

It’s rare that the theme for an entire year is set so early. But Zuck’s rollback of moderation, adoption of Community Notes, and decision to throw fact-checkers to the wolves set the tone for a year that saw digital deception legitimized, institutionalized, and shoved down the public’s collective throat. Platforms, tech companies, and AI giants failed to implement some of their key oversight initiatives and in some cases directly paid for, invested in, and otherwise incentivized manipulation.

In 2025, powerful people, companies, and institutions welcomed fakeness and deception like never before. The rest of us faced the consequences:

OpenAI’s Sora launched without basic guardrails against deepfake impersonation, a perfect encapsulation of the “ask for forgiveness, not permission" approach to consumer AI that has also included alleged mass copyright violations.

Meta welcomed a bevy of slop merchants and perhaps the most notorious online hoaxster in the US into its expanded Content Monetization Program, sending cash payments for their content each month.

Scams invaded our messages, feeds, and phones, fueling a $1 trillion global industry built on human trafficking, corruption, and the easy exploitation of digital platforms.

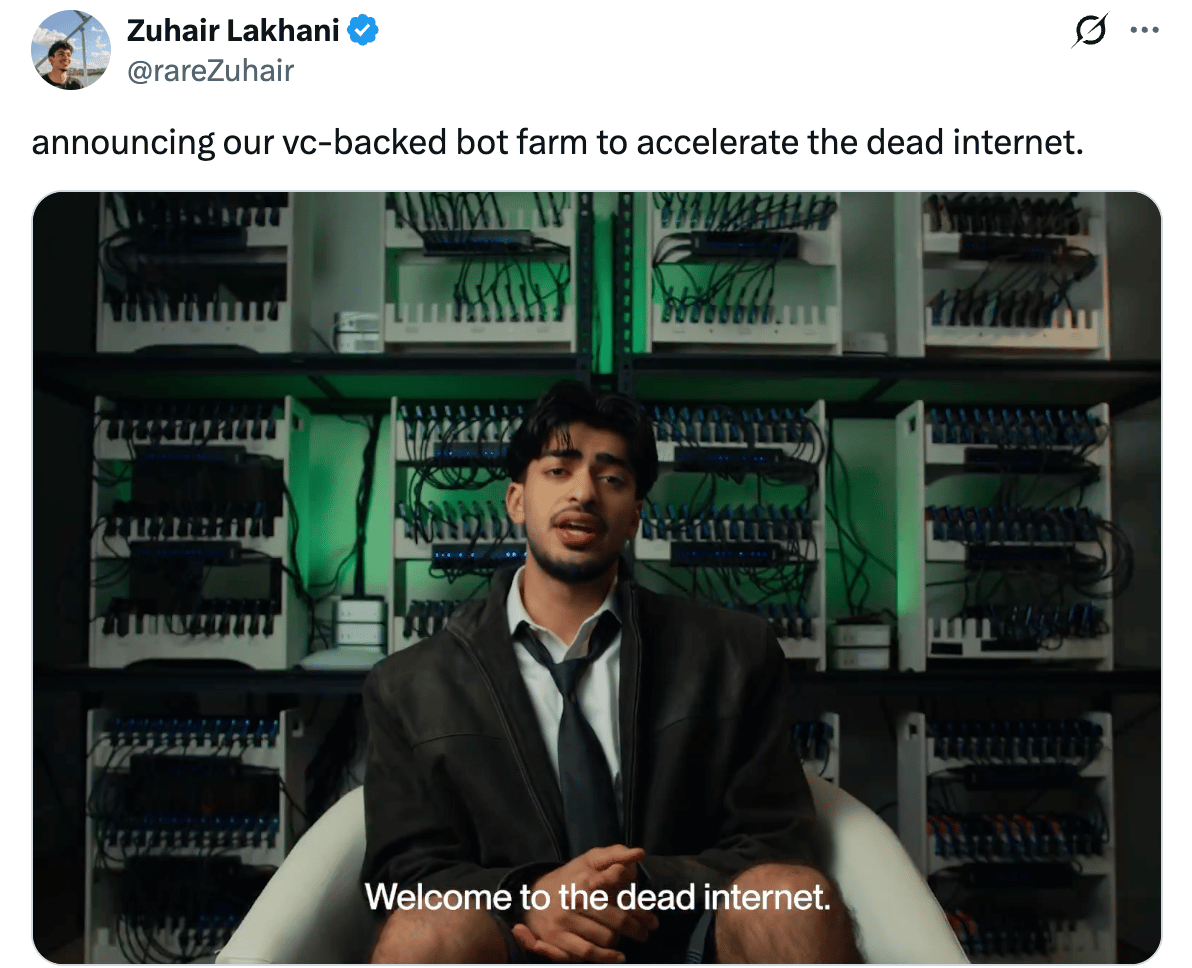

Investors, including Andreessen Horowitz, one of the world’s top venture capital firms, funded products and companies that engaged in, or enabled, deception and manipulation. That included putting $1 million into a TikTik bot farm and $15 million into Cluely, an app that started as a tool to help people cheat on coding interviews.

Lawyers and judges cited hallucinated case law hundreds of times, showing that even elite professions have become infected by the hype

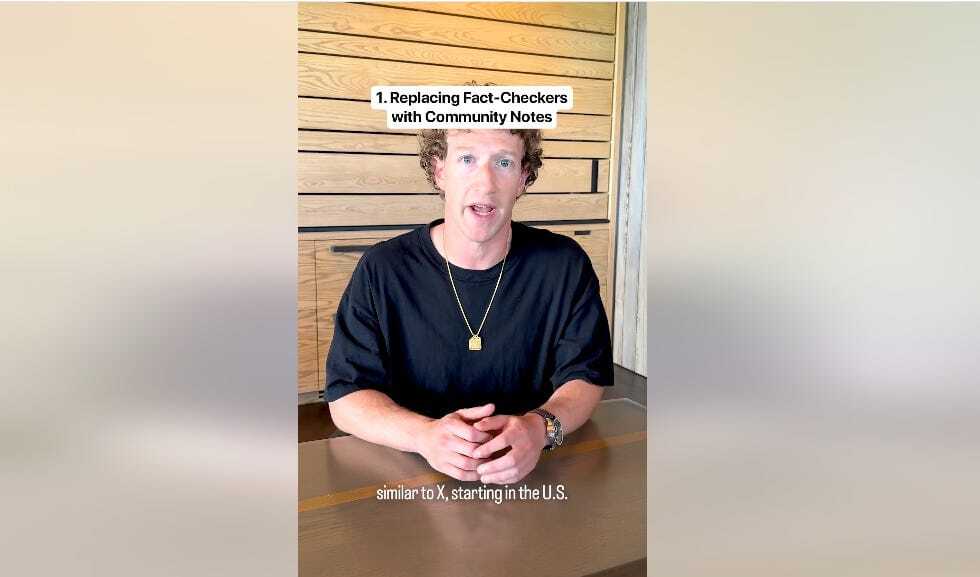

Abusive AI nudifier apps earned millions thanks in part to ads placed on Meta and apps on Apple and Google.

Tech giants filled social media timelines with AI slop in their quest to justify massive investment in compute and gen-AI products

Startups and vibe coding entrepreneurs embraced brainrot and ragebait, flooding social media with undisclosed ads and staged content, while platforms looked the other way.

The ethos of 2025 was embodied by the a16z partners that led the investment in Cluely, a company whose shitposting founder got kicked out of Columbia University. They said that his “bold approach may seem outwardly controversial” but praised his “deliberate strategy and intentionality.”

The lesson was that attention and engagement are king, regardless of how they’re generated or what they help promote. If you cheat or deceive — or, better yet, build a product that generates revenue from cheating and deception — you can reap the rewards.

In 2025, there was no shame in being shameless and exploitative. In fact, it could get you funded.

Cluely CEO Roy Lee

Red lines

This isn’t a defense of legacy media or an argument against innovation. It’s an objection to the legitimization, funding, and promotion of deceptive, misleading, and unethical online manipulation tactics. It’s a plea for some basic standards from people and organizations with incredible influence, resources, and power.

It’s not just platforms and tech entrepreneurs. A slew of newspapers reprinted a summer books feature that included AI-generated nonsense. A major newspaper in Pakistan published a business story that accidentally included a response from the LLM that generated the text. A town in the UK put up two massive Christmas murals that featured nightmarish AI slop scenes. The US president shared an AI-generated video that showed him dropping metric tonnes of shit on people.

Our information environment presents complex challenges and tough calls for platforms, governments, and other actors. There are difficult tradeoffs and technical limitations. Balancing the fundamental value of freedom of speech with legal compliance and the duty of care to users is hard. A lot of people inside tech companies are dedicated to tackling such challenges.

But some things aren’t complex. Incredibly, it seems necessary to say that you shouldn’t fund bot farms or send monthly cash payments to hoaxsters. It’s wrong to create powerful deepfake video technology and unleash it with little thought to how it will be weaponized. Don’t have a 17-strike policy for sex trafficking posts. Don’t tell regulators and the public that you’ll label AI-generated content and then fail to do so. Don’t allow fake reviews to flourish. Don’t say you’re replacing fact checkers with a “comprehensive” Community Notes program and then fail to invest the resources needed to make it useful or share any data about how it’s going. Don’t let your existing, pioneering Community Notes program wither, or turn it over to AI. Don’t mislead people by presenting ads as organic posts on TikTok and Instagram. And don’t allow scammers to place billions of dollars in ads on your platform in a single year.

One challenge is that the same companies that have poured billions into building AI tools also set and enforce the policies that govern their use. Meta, OpenAI, TikTok, and Google have a business imperative to get as many people using their AI tools as possible. The business needs will always win out, especially when regulators in the United States — where most of them are headquartered — have taken a mostly hostile approach to online safety. It’s why Zuckerberg began the year by aligning Meta with the “cultural tipping point” ushered in by Trump’s re-election.

2025 has felt like a tipping point. Or, more accurately, a reversal. Since late 2016, platforms emphasized how much they were doing to fight abuse and manipulation, even if the results weren’t always there. The pendulum has swung back. Perhaps it was inevitable. But you either care about information integrity or you don’t. Certain values and practices should hold firm, regardless of the political moment.

Here’s how the year played out.

Platform rollbanks and interventions

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

Zuckerberg’s January 7 announcement about eliminating the fact-checking program set the stage for a year of platform rollbacks. False or misleading claims shared on Meta stopped getting corrective labels in the United States in April. The company also stopped reducing the reach of false information. This was great news for pages that spread clickbaity hoaxes like America’s Last Line of Defense, which claims to be growing more than ever and earning money through the Meta’s Content Monetization Program. Vaccine misinformation is also resurgent.

Meta wasn’t alone. Google halted or reversed several smaller interventions. In January, it told the European Commission it wouldn’t integrate fact-checking into its platforms. In February, researchers discovered by accident that Google Search had stopped showing warnings for “quality voids,” which is when search terms return few reputable results. In June it stopped supporting Claimreview, the HTML code that helped surface fact checks in a structured way across Google products, including Google News and YouTube. (Disclosure: Alexios worked on several of those when he was at Google). In October, the company pulled the plug on a long-standing partnership to develop AI fact-checking with Full Fact, a British fact-checker. Google also announced it would give a “second chance” to YouTube creators it had previously banned for policy violations.

Both Meta and YouTube framed their policy changes as a concession to the White House. A congressional committee led by Jim Jordan – which has failed to find evidence of censorship – continued its efforts by targeting new platforms like Spotify, and by targeting the European Union’s Digital Services Act in a way that experts deemed flawed and misleading.

In March, OpenAI, the new giant on the content moderation block, rolled back its prohibition on generating photorealistic images of real people. This opened up the use of ChatGPT – and later, Sora – for impersonation. With OpenAI as cover, Google also rolled back its previous protections against impersonation, making realistic deepfakes of sensitive events easy for anyone to generate.

But there was some good news. TikTok’s updated community guidelines do not appear to have significantly shifted the company’s position on misinformation (though it’s hard to tell for sure from the outside). LinkedIn pressed on with its identity verification program, which it is now offering to other platforms. While we found that this program, too, can be abused, it’s a step in the right direction. Bluesky also invested significantly in verification, previously a major pain point for the platform.

The other big story was the expansion of Community Notes to new platforms. Meta and TikTok rolled out copies of X’s community-driven fact-checking effort. Unlike X, however, neither has shared data so we’ve had to make anecdotal assessments, even as Meta is asking the Oversight Board to weigh in on whether to bring the program to the rest of the world. The spread of such programs happened as X’s original effort may have peaked – outside of specific locales – and turned to AI contributors to prop itself up.

The battle between a deregulatory approach championed by Trump and a bureaucratic rules-based system driven by the European Commission and others around the world reached its zenith in December with the EU issuing a €120 million fine to X under the Digital Services Act. This was only in part a story about digital deception (and it is not a story about censorship). X’s transformation of the verification badge into a pure pay-for-play mechanism for amplification – which has led it to verify crypto-hawking fake Maltese presidents and AI nudifier apps – is one of three reasons the Commission issued the fine, alongside the platform’s refusal to share data with researchers.

The outcome of the transatlantic dispute over content moderation will determine whether 2026 sees more rollbacks or not.

Read more from Indicator:

AI is now baked into the workflows of information manipulation

AI adoption appears to be slowing down among businesses, with only 11% of respondents telling the US Census Bureau that they used AI to produce goods or services in the past two weeks.

One part of the economy appears to be all-in on general purpose AI, however: social media hustlers and slop purveyors. Open up TikTok and you will find AI-generated racist memes, crude recreations of dead public figures, and Elon Musk fanfic racking up millions of views. In February, we found that just 461 AI-generated videos of Elon Musk and Donald Trump giving motivational advice had been seen 700 million times.

Just about every social platform is in the same spot. One of the most rapidly growing creators on YouTube posts capybara brainrot (h/t Garbage Day). Instagram is flush in improbably endowed AI-generated thirst traps that are repped by agencies as if they were real. Users complain about slop outperforming human content on Pinterest, Reddit, and pretty much everywhere else.

Slop sometimes steals the content and credibility of real people, as with the dozens of accounts that used AI avatars of real journalists to spread fake news on TikTok, or YouTube channels that post fake disputes among prominent politicians.

Most AI slop doesn’t violate platform policies directly; instead, it hijacks the algorithms to make an easy buck. Platforms often welcome synthetic slop because it gins up engagement. Instagram’s decision to test AI comments show we’re approaching a full snake-eating-its-tail moment when AI content is boosted by AI-generated engagement.

All of this is just taking advantage of platform dynamics that rewards eye-catching and incendiary content that slows people down for the few seconds necessary to register as a monetizable view under Meta, TikTok, and YouTube’s advertising and revenue-sharing models. As 404 Media’s Jason Koebler wrote last month: “America’s polarization has become the world’s side hustle.”

Slop has also been adopted as an aesthetic, most notably by US President Donald Trump. He started the year by sharing a gaudy AI representation of Gaza as the Palestinian territory was being pummelled by bombs. He ended it with a deepfaked video of him unloading shit on American protesters.

Those dismissing AI slop as harmless should take note of Joe Rogan’s unintentional warning. In September, the popular podcast fell for an obviously AI-generated video of former Democratic vice presidential candidate Tim Walz. His producer corrected him on air but Rogan was unbothered. “You know why I fell for it?” he said. “Because I believe he's capable of doing something that dumb."

Platforms have done little to stop the onslaught of slop. Notably, Pinterest gave users the option to filter out AI content on some topics in October; TikTok is experimenting with a similar feature. Whether it works will depend on automated detection of synthetic content getting much better than it currently is, and on platforms delivering on their as of yet unfulfilled promise to label AI-generated content. YouTube also rolled out a pilot to let creators submit their biometric data to help the platform scan for impersonators. For now, this all feels like tinkering on the edges of an infrastructure set up to monetize and promote low quality AI-generated content.

Read more from Indicator:

We hope you’re enjoying this free post. Indicator is a reader-funded publication. If you become a member you can access all of our reporting about digital deception, our detailed OSINT and investigative guides, the Academic Library, and our live monthly workshops.

Nonconsensual deepfake nudes are still way too accessible

In some ways, it’s been a good year in the fight against AI-generated nonconsensual nudes. A key streaming platform for such videos shut down in May. The San Francisco City Attorney also shut down a company behind 10 AI nudifiers, and told us more settlements are coming.

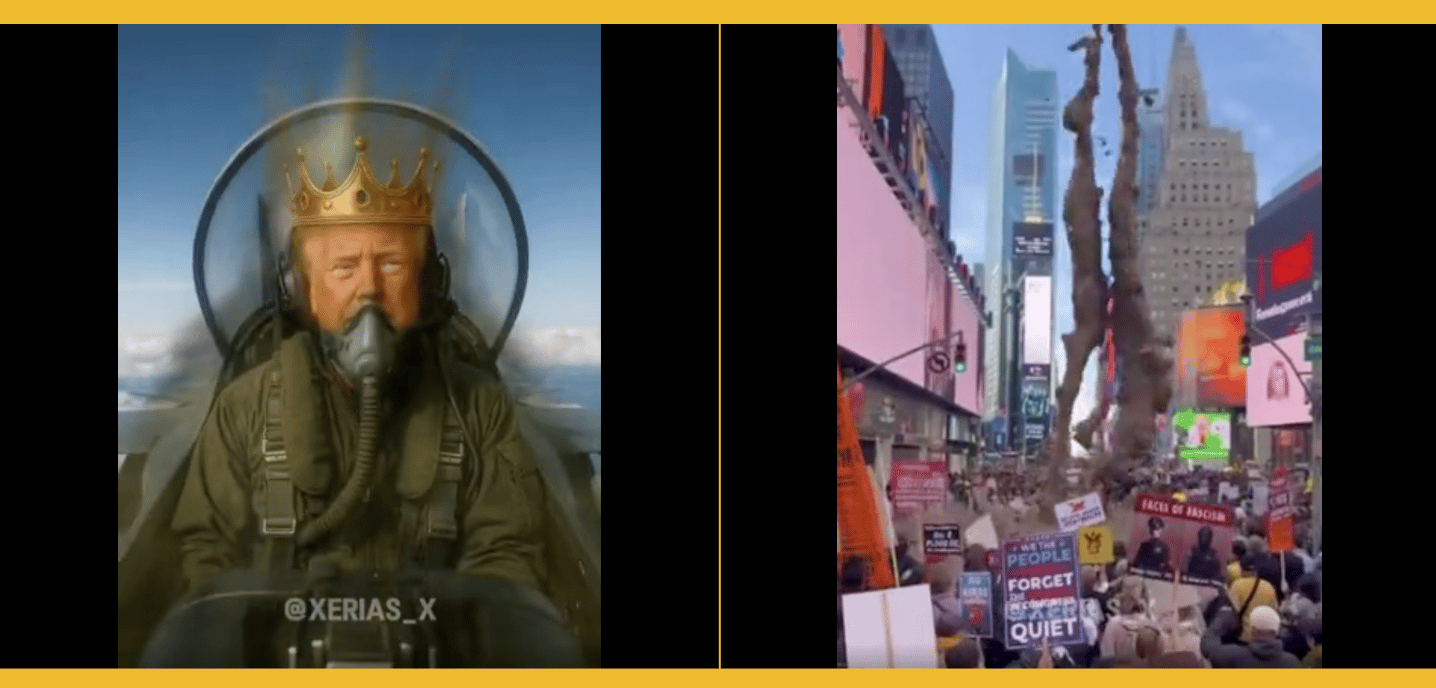

And yet this vector of abuse remains entrenched. Several teenagers in Calgary recently discovered they were targeted with nonconsensual AI-generated nudes. They join hundreds of known cases around the world and are likely only the visible minority of the full phenomenon. Indicator’s analysis in May found that top nudifiers reach millions and make millions. This is in good part because tech platforms are too timid or ineffective when going after them.

In the first half of this year, we found more than 12,000 ads for AI nudifiers running on Meta. After Meta announced it would sue the companies responsible and develop better classifiers to detect such ads, we expected things to improve. And yet we found 13,000 more ads after June, suggesting not enough progress was made. Worse, the advertisers take advantage of loopholes in Meta’s transparency tools to conceal their identity.

But Meta isn’t alone. Apple and Google continue to host “dual use” apps that present as playful faceswapping tools but market themselves elsewhere as generators of nonconsensual pornography. Data from Builtwith suggests that Amazon, Cloudflare, and other key tech service providers help keep nudifiers online.

As multiple experts told us, disabling the technology behind nudifiers will be very hard. Deplatforming should be the low-hanging fruit for tools that clearly market as nonconsensual intimate image generation. (Tackling AI porn sites that could be used b to create nonconsensual nudes will be harder still.) California’s AB 621, which was approved in October, makes tech platforms liable for providing services to AI nudifiers. Perhaps that will trigger a new level of enforcement in 2026.

Read more from Indicator:

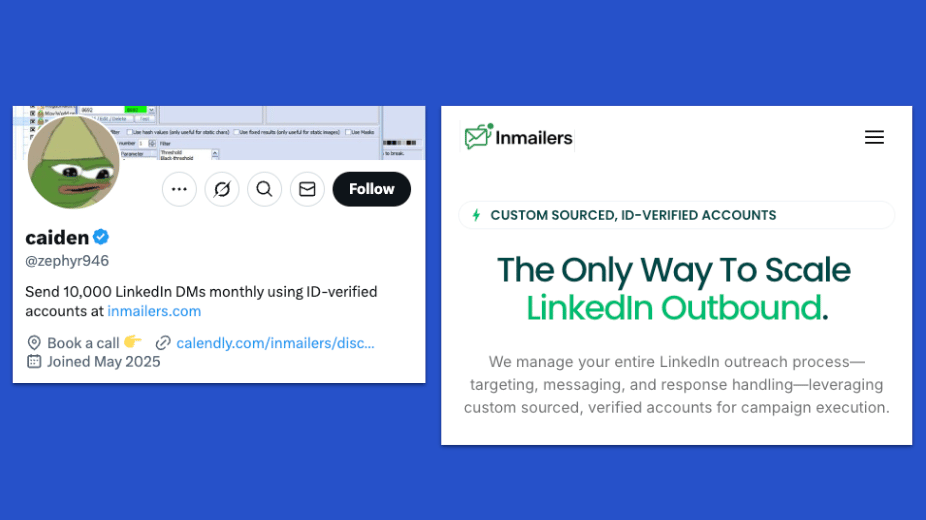

Ragebait and brainrot infected startups and digital marketing

In June, we published a story about a company that said it uses ID-verified LinkedIn accounts of attractive women to spam thousands of sales messages on behalf of clients.

“The best converting persona I’ve ever built was a divorced 42-year-old woman named Claire who used to work at HubSpot,” said Caiden Glasier, the cofounder of the company, in one of his typically braggadocio filled posts. “I miss her every day.”

Glasier posted frenetically on X about how they’d found a way to blow past LinkedIn’s direct messaging limit and were making bank thanks to “fake female linkedin accounts spamming dms to boomers.” But when we spoke to his co-founder in May, he said they didn’t use fake accounts — it was just a marketing ploy.

“Almost everything in those tweets is not true and fully satire and we make sure the clients know when they are on the call,” said Andrej Simunovic. (Glasier’s X account was eventually suspended for unknown reasons.)

It’s unsurprising that people who built a product that violates LinkedIn’s terms of service would embrace deceptive marketing. But such tactics, and products, have moved from the fringes to the mainstream.

Along with an Andreessen Horowitz-funded bot farm and cheating app, a “brainrot code editor” called Chad IDE was accepted into Y Combinator, arguably the most prestigious startup accelerator in the world. An AI-powered study app placed thousands of undisclosed ads on TikTok and Instagram, including staged confrontations between students and professors/TAs. Another study app used undisclosed ads to direct students to fuckingstudy.com, which created a "brainrot" version of its product that could “transform your boring-ass PDF documents and text files into UNHINGED, outlandish short lecture videos.”

It got to the point that someone launched a satirical website for a VC firm with a brainrot investment thesis: “Brainrot represents the final, logical endpoint of the attention economy: The maximum return on investment for minimum cognitive effort.”

It’s not do different from the kind of thing you’d see a vibe coder or venture-funded entrepreneur say on X these days.

But credit to Jordi Hays of TBPN — the fast-growing tech live stream show — for calling it out. In November, he declared on the show that “ragebaiting is for losers”:

In 2025, rage baiting has become a product strategy. Cluely started as an app for cheating on coding interviews. Chad IDE’s only known differentiation from the other hundred AI native IDEs is that you can gamble and swipe on dating apps in it. The rage bait is sitting at the product level now.

His TBPN cohost John Coogan made a similar point:

If you put 1% of your fund into something that is just going to go all over the internet and be like, we're the most degenerate, we're the craziest, we're the most insane, we're the most fraudulent, like in your face company … well, if that 1% gets a thousand times more views than your enterprise SaaS portfolio, like you're going to be known as the slop fund.

Read more from Indicator:

Digital scams scaled to new heights

An aerial photo taken on September 17, 2025 shows the notorious KK Park scamming complex in Myanmar's eastern Myawaddy township. Photo by Lillian Suwanrumpha AFP via Getty Images

For roughly 40 years, experts and the media have used the term “narco-state” to describe a country whose institutions and economy have become intertwined with illegal drug trafficking.

This year we saw the true emergence of the “scam state,” where “an illicit industry has dug its tentacles deep into legitimate institutions, reshaping the economy, corrupting governments and establishing state reliance on an illegal network.”

That’s how The Guardian described the situation in the Mekong region, where corruption and apathy have enabled scores of scam compounds to operate 24/7. It’s a chain reaction of horribleness: people are trafficked to compounds where they toil in a new form of slavery to try and steal money from victims all over the world.

One positive this year was that some of the most notorious compounds were raided and supposedly shut down. Governments in Thailand and elsewhere are taking action. And the US government brought its first major case against a group that has allegedly operated such compounds.

But make no mistake: the compounds will continue, along with myriad other schemes and operations. Digital scamming is a global industry built on organized crime, digital marketing, money laundering networks, trafficked and indentured labor, and rapid technological adaptation and iteration. Scamming has been revolutionized by technology, and 2025 saw even more nightmarish innovation.

Advancements in AI have made it cheap and easy to scale scamming while also making it more convincing. Romance scammers and pig butcherers can hold deepfake video calls with victims. Phone scammers can clone the voice of a relative or work colleague. It’s trivial to copy a corporate website or ad, or to register thousands of domains to assist with a large-scale ecommerce scam. You can reach victims via targeted digital ads or blast out text messages using SIM card farms or SMS blasters.

Thanks to Jeff Horwitz at Reuters, we learned that internal Meta documents estimated that as much as 10% — or 16 billion — if its annual revenue could come from scam ads. A Meta spokesperson said the 10% figure was “rough and overly-inclusive” and that the documents “present a selective view that distorts Meta’s approach to fraud and scams.”

But it’s clear that the company earns billions a year from scam ads — and keeps the money even when it removes such ads. Two examples from this year illustrate how pervasive scam operations are:

Maldita documented a multilingual and multinational Facebook scheme where scammers created Facebook pages that impersonated local transit authorities in dozens of countries. The pages ran ads that enticed users with low-cost transit passes, which led people to hand over their credit card information.

News organizations in several countries reported on the phenomenon of “ghost stores” that presented themselves in Meta ads as locally-owned businesses. In reality, they used AI-generated images of the owners and physical stores. People bought bags, shoes, and clothes because they thought that they were supporting a local business in trouble.

In 2025 scammers relentlessly scaled up their use of AI, digital ads, mass SMS messaging, and app marketing to ensnare more people than ever before. And while governments are beginning to mobilize, we’re still waiting for the moment when platforms declare war on scammers, meaningfully invest in prevention, and start disgorging money earned from scam ads.

Maybe in 2026?

Read more from Indicator:

Indicator is a reader-funded publication.

Upgrade to access all of our reporting on digital deception, our detailed OSINT and investigative guides, the Academic Library, and our live monthly workshops.