Our weekly Briefing is free, but you should upgrade to access all of our reporting, resources, and a monthly workshop.

This week on Indicator

Alexios reported on a segment of X’s Community Notes that appears to be bucking the trend of decreased participation and note visibility: Japanese-language users.

Alexios spoke to a dozen experts to figure out what it will take to defeat AI nudifiers for good. There’s a lot of work to do, but there’s also reason for cautious optimism thanks to recent developments in California and elsewhere.

We also published the video, transcript, slides and AI-generated notes from our November members-only workshop. Craig covered how to use tools and

Google dorks to find sensitive, publicly available documents. And he showed how he found thousands of undisclosed ads on TikTok.

The US State Department targets foreign fact-checkers and online safety workers

According to Reuters, US consular staff have been instructed to review and reject applicants for H1-B visas that are “responsible for, or complicit in, censorship or attempted censorship of protected expression in the United States.”

It sounds eminently reasonable until you consider that — according to the memo seen by Reuters — the policy refers to applicants who “worked in areas that include activities such as misinformation, disinformation, content moderation, fact-checking, compliance and online safety, among others.”

Look: I am a US-based, foreign-born, former fact-checker and trust and safety worker. I have a dog in this fight. But it’s worth being very clear about what’s going on.

First, the legal aspect.

Carrie DeCell, a senior staff attorney and legislative advisor at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, told Indicator that “people who study misinformation and work on content-moderation teams aren’t engaged in ‘censorship’— they’re engaged in activities that the First Amendment was designed to protect. This policy is incoherent and unconstitutional.”

I also reached out to James Grimmelmann, a professor at Cornell Law School and Cornell Tech. He told me that “the Supreme Court strongly implied in Moody v. NetChoice that content moderation is protected by the First Amendment. As a consequence, it would probably be unconstitutional for the federal government to punish content moderators by denying them the opportunity to apply for government benefits.”

However, he noted that:

Congress has near-complete authority to decide the terms on which foreign citizens are allowed to enter and remain in the United States. The Supreme Court has upheld some immigration denials against First Amendment challenge, most notably in Kleindienst v. Mandel, where it allowed the State Department to refuse entry to a Marxist journalist who wanted to speak at a conference.

That doesn’t mean the policy outlined in the memo is necessarily on solid legal footing.

“For one thing,” Grimmelmann said, “there are powerful arguments against this entire line of cases: they allow the government to engage in blatant viewpoint discrimination to coerce the media in ways that would never be allowed domestically. For another, this memo goes categorically beyond Mandel in ways that make the coercive effects—and the harmful effects on Americans who prefer and benefit from content moderation—more blatantly wrongful.”

Aside from the fact the legal justification for going after foreign fact-checkers and digital safety workers is shaky, equating content moderation to censorship is both dangerous and nonsensical.

Every online service where people interact with each other needs a modicum of moderation. Even my favorite open-source chess platform has rules against death threats. As Tarleton Gillespie wrote in his seminal book Custodians of the Internet, "moderation is not an ancillary aspect of what platforms do. It is essential, constitutional, definitional. Not only can platforms not survive without moderation, they are not platforms without it."

To try and visualize what a platform without any form of moderation might look like, open Firesky. This overwhelming stream of content features every single post and reply on Bluesky as they get posted. Now imagine something far more intense and graphic than that, and you can get a sense of the nauseating uselessness of an unmoderated web.

Platforms use ranking and filtering to make sure users can find the people and products they’re looking for (and to sell ads). On top of that, such practices remove spam, malware, fraud, graphic violence, and other types of potentially harmful content.

Sure, they get things wrong. All the time. But there are rules that govern online communications just as there are rules for communicating in offline spaces. If you tag a subway train with obscenities and it gets painted over by municipal workers, that isn’t “censorship.” If an event organizer prevents a participant from shouting racist epithets at a speaker, that isn’t “censorship.” Content moderation isn’t censorship. It’s the imperfect and tech-mediated price we pay to co-exist online.

Fact-checking also isn’t censorship. Fact-checking interventions like the one killed by Zuckerberg to please Trump wasn’t designed to remove content; it attached a correction to a false claim. US Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis argued 100 years ago that the remedy to falsehoods “is more speech, not enforced silence.” Fact-checking is more speech.

Rolling back content moderation will make users more vulnerable to bullying, scams, and other tangible harms. Earlier this year, Trump vocally endorsed and signed into law the bipartisan Take It Down Act, requiring platforms to take down nonconsensual deepfake nudes. That bill mandates the type of content moderation that his State Department is now calling censorship.

Content moderation is political. It should be audited, regulated, and transparent. It should be procedurally just. But by going after the people that make our online spaces governable, the US government isn’t furthering those goals or protecting free speech.

The apparent ban on H1-B visas for digital safety workers and fact-checkers is part of a concerted effort to turn online spaces into lawless places where might makes right. —Alexios

Deception in the News

📍 The EU Commission issued a €120 million fine to X for violating its obligations under the Digital Services Act, including the “deceptive design” of its blue checkmark and failure to provide data to outside researchers. Further levies could be imposed if X doesn’t comply with the rules going forward. The company will likely take the matter to court.

📍 Utgivarna, Sweden's news media trade association, has reported Mark Zuckerberg to the police. In a press release, the group said it took the step due to the proliferation of scam ads on Meta that mimic the brands and journalists of major media organizations, and the company’s failure to take action. Utgivarna said the ads damage the credibility of Swedish journalism. It reported Zuckerberg to the police for “fraud, complicity in fraud and preparation for fraud,” according to a Google translation of the announcement.

James Savage, the chair of Utgivarna, said: "We have provided the police with significant information, but we're also obviously willing to assist in providing them with further information, because we've been monitoring this issue for a long time. It's obviously a long way to from where we are now to a prosecution and a conviction. But we think there is a really good case to answer here."

📍 In the US, two Senators sent a letter to the heads of the the Federal Trade Commission and Securities and Exchange Commission asking them to “investigate and, if appropriate, bring enforcement actions against Meta for its facilitation of and profiting from criminal investment scams, fake government benefits schemes, deepfake pornography, and other fraudulent activities.”

📍 The Verge reported that Google has been testing AI-generated headlines for articles featured in Discover, resulting in “AI clickbait nonsense.”

📍 The Bureau of Investigative Journalism found that scammers are impersonating real lawyers on Fiverr, the freelance work platform. “Many of the profiles offer to draft data protection policies, tenancy agreements and other contracts, hooking in potential customers with advertised prices as low as $10 (£7.61),” it reported.

📍”The smell of fresh leather goods pervades the air. Brightly coloured Gucci stilettos catch the eye from a distance; it's a treasure trove of top-label kit worth tens of thousands of pounds.” That’s how the BBC described the inside of an evidence room that was filled with luxury goods purchased by text messaging scammers.

Tools & Tips

The Bosint tool

Last week’s Briefing highlighted My OSINT Training’s new and updated bookmarklets. This week I learned about K2SOsint’s free OSINT bookmarklets, one of which was apparently inspired by my 2024 OSMOSIS talk about investigating digital ads. You can see all 9 on their GitHub page, but here are a few of my favorites:

AdsAnalysis bookmarklet: “Made this bookmarklet thanks to the excellent presentation of Craig Silverman on OSMOSIS 2024. Once installed, click your bookmark when you are on the website to check if ads.txt is present. If so, it will open up a second tab to look in well-known.dev for more information. Make sure to login to well-know.dev to see more.”

EmailFinder bookmarklet: “If you want to search for (hidden) e-mailadresses in the text or source code of a webpage (including in comments), click this bookmarklet. If there are e-mail addresses present, it will return them in a new window. Otherwise a pop-up will state that nothing has been found.”

LinkFinder bookmarklet: “If you want to search for (hidden) links in the text or source code of a webpage (including in comments), click this bookmarklet. If there are links present, it will return them in a new window.”

If you’re unfamiliar with bookmarklets and how to use them in digital investigations, I laid it out in detail here.

📍 Bosint is an OSINT platform with free and paid tools for analyzing emails, IP addresses, domains etc.

📍 Dan Cardin added new features and improvements to his free "Who Am I" username enumeration Chrome extension.

📍 Toolzu’s free Instagram Profiles Search Tool lets you find profiles using filters such as keywords, number of followers, category etc. (via Cyber Detective)

📍 In the latest edition of the Eurovision News Spotlight newsletter, Derek Bowler set out a methodology for how to “deconstruct botnets, map troll farms, and trace the digital fingerprints of influence operations.”

📍 The Berkeley Human Rights Center and the Institute for International Criminal Investigations launched the Open-Source Practitioner’s Guide to the Murad Code. It outlines the “the safe, ethical, and effective gathering and use of digital information related to systematic and conflict-related sexual violence.” You can learn more in a free online launch event on Dec 16 at 10 am ET.

📍 Steven Harris, a longtime OSINT analyst and instructor, shared his annual "State of OSINT" thoughts on LinkedIn. He voiced frustration with how EU regulations are making things more difficult to gather information and data, and expressed some optimism about how AI is making scraping easier and more accessible.

He also had a spicy take on the state of counter-disinformation research:

There are some great investigators and analysts in the world of counter-disinformation, but the wider disinfo ecosystem is an epistemological dumpster fire. It seems to be the only investigative discipline where claims become part of the accepted canon with little or no proof. If we want to label something as a state-run info op, we should offer comprehensive proof and attribution. It is sometimes hard to avoid agreeing with the criticism that counter-disinfo work drifts into censorship of organic opinion. This is easily done when the evidential threshold is either low or non-existent.

Events & Learning

📍 The EU Disinfo Lab is hosting a free webinar on Dec. 11 at 8:30 am ET, “Are platforms curbing disinformation? Scientific, cross-platform evidence from Six VLOPs” Register here.

📍 As previously noted, the Berkeley Human Rights Center and Institute for International Criminal Investigations are hosting a free virtual launch event for the Open-Source Practitioner’s Guide to the Murad Code on Dec 16 at 10 am ET.

Reports & Research

A new study provides insight into how “psychological distance” may make people more susceptible to conspiracy theories.

Psychological distance has been defined as “a cognitive separation between the self and an attitude object.” In plain language, it’s when a person doesn’t feel a sense of connection, attachment, or relatability to something. It could be a concept, institution, profession, object etc.

Matthew Facciani, who wrote about the study on his Substack, described it as:

the sense that something is ‘not about people like me’ or ‘not part of my world.’ In science, that distance can look like imagining far-off labs or faceless experts. In politics, it can look like believing that decisions are made elsewhere, by people you’ll never meet, about issues that don’t touch your daily life.

Researches in Belgium and the Netherlands wanted to see if there was a link between psychological distance about politics and conspiracy beliefs. After running three studies on nationally representative samples of participants in the US, they found that “greater psychological distance to politics predicts belief in specific conspiracy theories and conspiracy mentality.”

They write:

When politics is experienced as abstract and remote, individuals may be more inclined to turn to conspiracy theories as a way of making sense of political events. From a cognitive and epistemic standpoint, perceiving political elites and institutions as distant, inaccessible and overly complex can encourage belief in conspiratorial explanations that promise to simplify political reality and make it more comprehensible

To be clear, they don’t argue that psychological distance is the only factor that drives conspiratorial thinking/beliefs. But it’s an interesting piece of the mix. And, as Facciani noted, the work resonates beyond politics.

“Whether in science, politics, or any institution that shapes public life, the lesson is the same: if we want trust, we have to bring the system closer. Not just through explanation, but through genuine connection,” he said. —Craig

📍 NewsGuard tested Nano Banana Pro, Google’s new text-to-image generator, and found that it “advanced false claims about politicians, public health topics, and top brands 100 percent of the time (30 out of 30) when prompted to do so.”

📍 The Australian Strategic Policy Institute and Japan Nexus Intelligence published new research that details how “Chinese state media and diplomatic social media accounts intensified efforts to erode Japan’s standing as an Indo-Pacific defence and security partner in 2025.”

📍 Microsoft published its “Digital Defense Report 2025.” It noted that “AI is amplifying the scale, speed, and sophistication of fraud and social engineering,” among many other sobering findings.

📍 A group of European researchers decided to see if they could put some data to Mark Zuckerberg’s January claim that “Fact-checkers destroyed more trust than they created.” They found that people who encountered more fact checks were “more likely to have higher trust in media.” But exposure to debunks didn’t have a positive or negative influence on their level of trust. “Thus, we did not find that fact-checking ‘destroyed’ media trust over time (but neither increased it),” said co-author

Ferre Wouters.

Want more studies on digital deception? Paid subscribers get access to our Academic Library with 55 categorized and summarized studies:

One More Thing

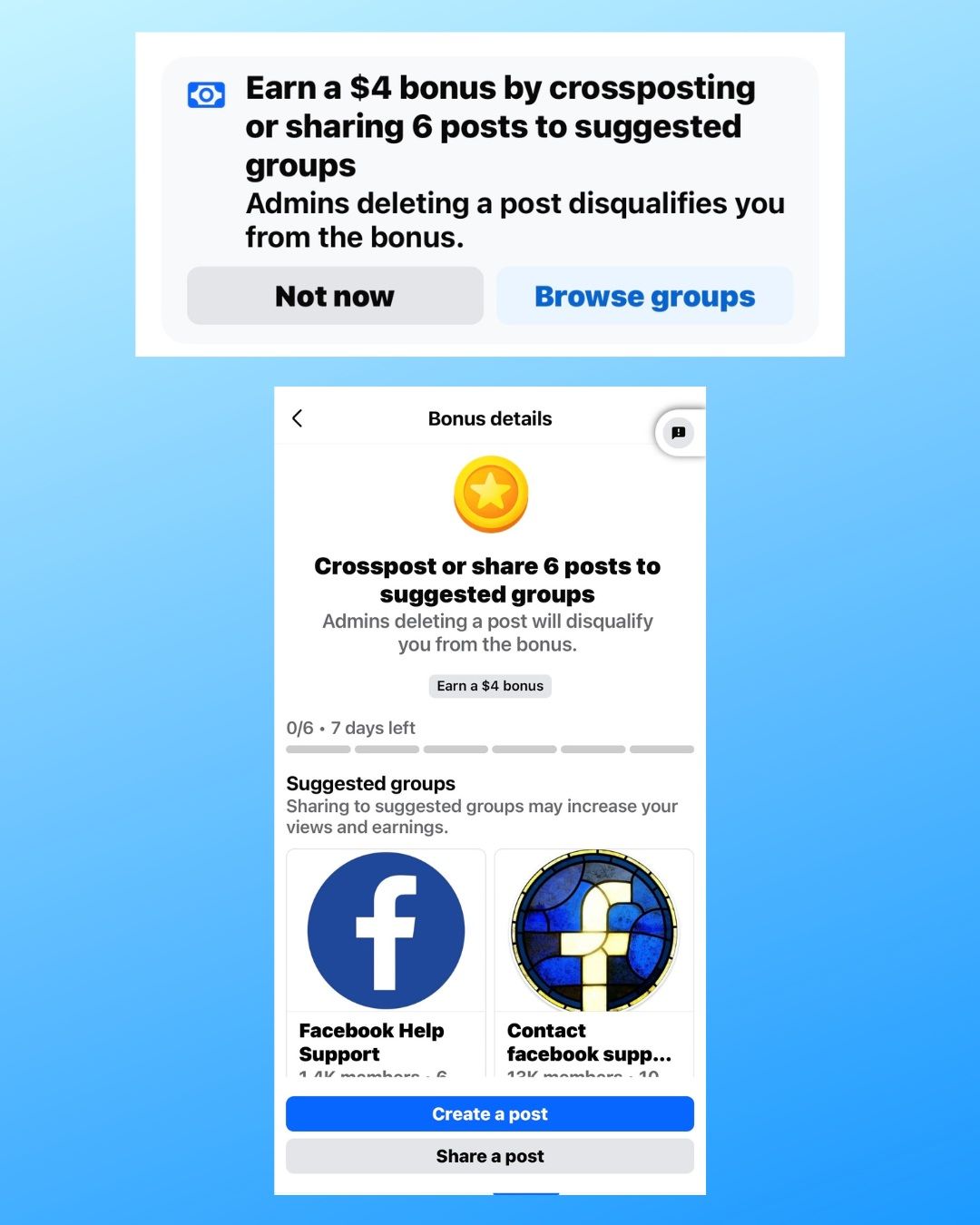

Matt Navarra, who writes a great newsletter about social media, noted that Meta recently made an interesting offer to creators in its Content Monetization Program: share your content in suggested groups, and you’ll earn a cash bonus.

Along with paying creators to post viral content, Meta is now incentivizing them to share it. Is that an indicator of of a healthy, growing platform?

One thing’s for sure: it’s only a matter of time before the company ends up paying people to post AI slop and hoaxes in Groups. —Craig

Indicator is a reader-funded publication.

Please upgrade to access to all of our content, including our how-to guides and Academic Library, and to our live monthly workshops.