Hey there, Indicator is a tiny operation — just Craig and I — and paid memberships keep it going. We’re offering 20% off for one week; consider upgrading now to support our work and get discounted access to all of our reporting.

The video seems familiar at first. Renée Good smiles at the camera from the driver’s seat of a maroon car, her arm resting on the open window. As she drives away, however, Good starts singing “Ice Ice Baby,” and pumping her arm to the rhythm of the 1990 rap song.

In another synthetic video, Good says that “my pronouns are was/were. It’s really hard to drive when you have a splitting headache so I got in a wreck on Wednesday. I guess you could say I fucked around and found out.”

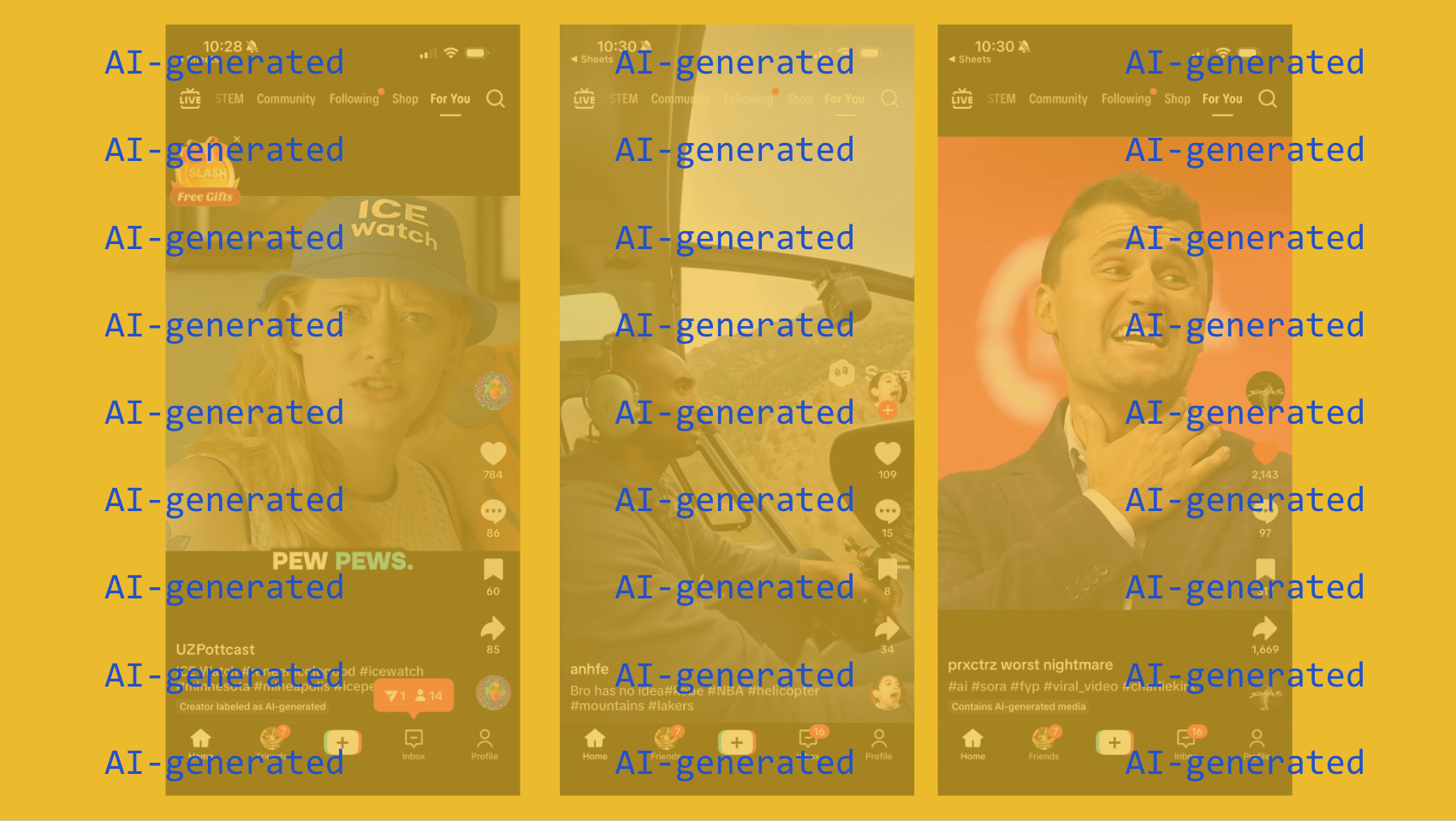

These are two of more than 20 videos1 Indicator found across Instagram, TikTok, X, and YouTube that use AI to impersonate the woman killed by ICE officer Jonathan Ross in Minneapolis on January 7.

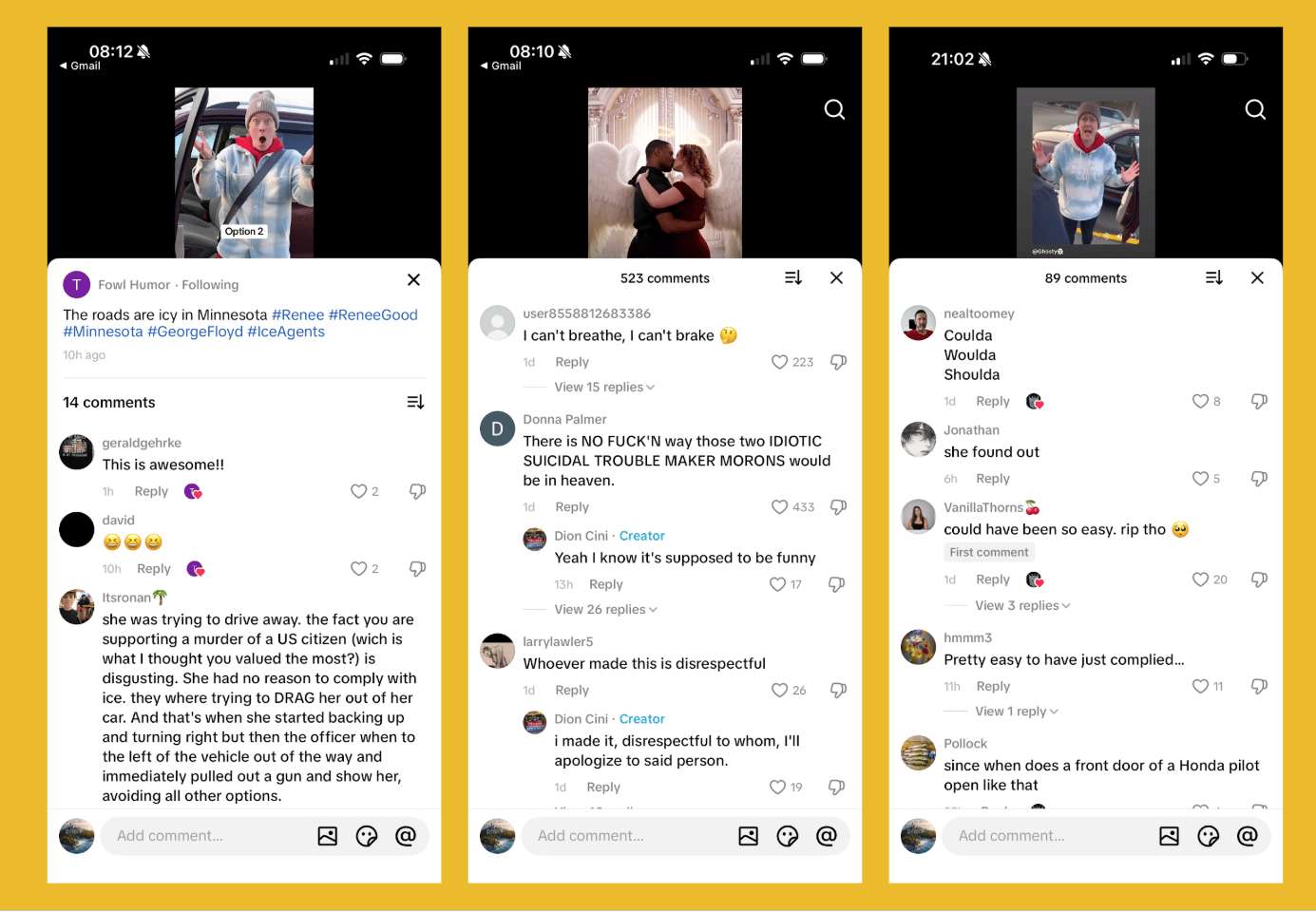

Videos show Good in her car wearing a sweatshirt that says “FAFO” or kissing George Floyd. Another depicted her lying on the floor with the ICE officer’s knee on her neck, in a macabre recreation of Floyd’s own murder. Commenters piled on with further mockery.

Good isn’t alone. Indicator found dozens of deepfakes of individuals who met a tragic death in recent years, including Kobe Bryant and Charlie Kirk.

(TikTok deleted 41 out of the 102 videos Indicator flagged to the company ahead of publication of this article and added AI labels to others. Meta said it would review the four videos we shared. YouTube determined the three videos we shared did not violate its policies but applied an AI label to one of them.)

This use of deepfakes to mock a tragic death, which might be described as “digital desecrations,” is an extreme version of a pervasive phenomenon of the generative AI era. When OpenAI launched its Sora social app late last year, “resurrections” via deepfake were a popular trend. The loved ones of Robin Williams, Martin Luther King Jr., among others, were appalled.

But the videos Indicator found aren’t merely distasteful and nonconsensual. They mocked the fact and manner of their subjects’ death.

I reached out to six AI, media, and ethics scholars to get a better sense of the novelty of this phenomenon, whether AI has desensitized us to representations of dead people, and what tech platforms should do about such content.

They told me that over the centuries, images of the dead have been misrepresented and exploited for commercial or political reasons in political cartoons, state propaganda, tabloid reporting, and seedy websites.

“Public death has long been a site of spectacle and power, and mockery of the dead predates the internet” said Julie Carpenter, external research fellow at the Ethics + Emerging Sciences Group and author of The Naked Android.

As the information studies scholar Tonia Sutherland writes in Resurrecting the Black Body, “lynching in the United States was a lucrative photographic endeavor […] it was common for white Americans to send their loved ones picture postcards of lynchings they had witnessed and photographs of themselves posed with hanging corpses.”

Tamara Kneese, author of Death Glitch, told Indicator that while generative AI may have extended the “ubiquity and reach” of digital desecrations, “trolls have long used social media platforms to harass the family members of high-profile murder victims.”

Akiko Orita, a communication professor at Kanto Gakuin University, pointed me to Rotten.com, a website active between 1996 and 2012 that hosted macabre images of the dead and dying. “Desecration does not happen only through technical photo editing,” Orita says. “It can also happen in the way people represent or frame the dead.”

By this reading, deepfake desecrations are the latest step in what sociologist Michael Hviid Jacobsen has called “the age of spectacular death.” Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska, a researcher on technology and death at Cambridge University, defined this phenomenon as “a cultural condition in which death is made highly visible and emotionally engaging, yet often stripped of depth and responsibility, functioning more as a media event than a shared social experience.”

Still, the experts I interviewed agreed that something has changed with generative AI.

What’s new, according to Carpenter, “is the medium’s claim to presence. AI impersonation shifts desecration from depicting someone to ventriloquizing them: synthesizing face, voice, and affect and then staging ‘new’ actions, lines, and reactions. That’s not just cruelty; it’s an authored performance that borrows the authority of the person’s likeness.”

AI also enables digital desecration at greater scale and immediacy.

Join Indicator to read the rest

“I’m a bit more at peace knowing there are people out there doing some really heavy lifting here - investigating, exposing, and helping us understand what’s happening in the wild. And the rate & depth at which they're doing it..." — Cassie Coccaro, head of communications, Thorn

Upgrade nowJoin Indicator to get access to:

- All of our reporting

- All of our guides

- Our monthly workshops